OSS / SOE Yugoslavia 1944

OSE on Tito's lines

In Yugoslavia, the goals of the OSS were to help the

resistance forces to sabotage railroad lines carrying supplies into Germany, to

tie down tens of thousands of German occupation troops and prevent them from

being used on the front lines against the Allied armies. In addition, the OSS

in Yugoslavia rescued aviators who had been shot down on the bombing runs from

Italy to the Ploesti oilfields in Rumania, and it also sought to deceive Hitler

into thinking that the American invasion might occur in the Balkans instead of

in Normandy. The Germans had invaded Yugoslavia in the spring of 1941 and

occupied the most populated areas of the country, but a substantial Resistance

movement quickly emerged and took refuge in the sparsely settled mountains.

The

movement split between the Partisans under Communist Party leader Josip Broz

(“Tito”), a Croatian, with their core area in the mountains and forests of

northern Bosnia, and the Royalist Chetniks under Yugoslavian General Draža

Mihailović, a Serb, who operated out of their base in the wooded mountains of

Montenegro in the south.247 Bitter enemies, they fought each other as much as

the Germans. Among the undercover operations by the Western Allies, Britain

initially had a monopoly in the Balkans, but in the late summer of 1943,

Donovan was able, despite SOE objections, to begin sending OSS operatives into

Yugoslavia to establish connections and sources of information independent of

the British. In the third week in August, two OSS Special Operations officers

were airdropped, one into the headquarters of each of the two hostile factions.

Army Capitain Melvin O. (“Benny”) Benson was infiltrated into Tito’s

headquarters; and Marine Captain Walter R. Mansfield was air dropped into

Mihailović’s camp.

Parachuting alone into the area near Mihailović’s base just

before midnight on 19 August 1944, Mansfield was a highly regarded SO officer.

A Boston native, Harvard graduate and a former member of Donovan’s law firm,

the 32-year-old Mansfield had joined the OSS as a civilian. But he had attended

Marine Reserve Officer class and also learned demolitions and guerrilla warfare

at OSS SO training areas in Maryland, Virginia, and England. Accompanying

him were 15 canisters filled with small arms, radios, and three tons of

ammunition.

A few minutes after he landed amidst the bonfires of the drop zone,

he was surrounded by a small group of ragged-looking men with black beards. “I

told…their leader that I was an American,” Mansfield recalled, “whereupon they

all began to shoop, holler, and kiss me (black beards and all) shouting

‘Zdravo, Purvi Americanec’ (Greetings, first American). I mustered up my

Serbian to reply, ‘Zdravo Chetnici’—the first American had landed.” Mansfield was later joined by Lieutenant Colonel Albert B. Seitz and Captain

George Musulin, an American of Serbian ancestry. All three were much impressed

by the Chetniks.

Allied action in Yugoslavia remains controversial. Leftists

among the British SOE mission attached to Tito emphasized the superiority of

his forces, overstating the communist partisans’ numbers and accomplishments,

while denigrating the Chetniks. Although London cut off supplies to

Mihailović, the OSS argued that both Yugoslavian factions were effective and

should be aided in their separate areas of control—Tito in the north and west,

Mihailović in the east and south. Captain Mansfield wrote strong endorsements

of the Chetnik leader. Yugoslavs loyal to the monarchy and Mihailović had been

among the foreign groups trained at OSS Area B. But at the Tehran conference in

November 1943, Stalin and Churchill backed Tito and insisted that Roosevelt cut

off all support for Mihailović. Despite Donovan’s protests, the American OSS

mission to Mihailović were forced to leave the Chetniks in the early months of

1944.

SOE and SIS assisting Serbian insurgents 1943

Tito and his Partisans had their admirers in the OSS.

Captain Benson was the first, followed by Lieutenant Colonel Richard (“Bob”)

Weil, Jr., 27, a former President of Bamberger department stores, a division of

R.H. Macy and Company, who accompanied one of the OSS mission’s to Tito.254 In

November 1943, Lieutenant George Wuchinich, a second-generation American from

Pittsburgh whose parents had been Orthodox Serbs from Slovenia, and who had

trained in1942 at Areas B, A, C, D and RTU-11, led the “Alum” Team that was

parachuted into Partisan-held territory in the mountains near Ljubljana in

Slovenia in November 1943, the first OSS team to arrive in northern Yugoslavia

(Tito’s headquarters was farther south).

Wuchinich was accompanied by a Greek-American

radio operator, Sergeant Sfikes, and four other enlisted men. He found the

Partisans suspicious of both the British and the Americans. But when Wuchinich

was finally allowed to meet the local general and accompany the Partisans into

battle against the Germans, he became glowing in his reports. Indeed, he

compared them to the dedicated, long-suffering Continentals in the American

Revolutionary War,

Finally, in June 1944, Wuchinich gained enough trust to

be allowed to pursue his assigned mission—to secure daily reports to OSS on the

main Balkan railroad system which ran through Maribor at the Slovenian-Austrian

border before dividing into separate main lines to Italy and Greece. Trekking

through the mountains, they established an observation post overlooking Maribor

and then returned to camp. From 30 June through 4 August, the observation post

sent as much detailed information about troops and supplies going through the

throat of the southeastern European rail network as the Allies could desire. The

Germans finally located it, killed the radio operator and seized his equipment,

but the Allies had gotten the information during period immediately following

the Normandy invasion, which is when it was most needed.

Wuchinich’s team

also gained valuable information from a deserter about the development and

proving ground for the new “flying bomb,” the V-1 “buzz bomb,” rocket the

Germans began to launch against England in mid-1944; and they helped rescue

more than a hundred downed Allied aviators. Wuchinich’s reinforced team did

suffer casualties, however; at least two of the Americans were killed.

Activity by the OSS increased dramatically in Yugoslavia in

1944, especially support for Tito and his Partisans. The number of OSSers

attached to the Partisans grew from six in late 1943 to 40 men in 15 different

missions in 1944. Major Frank Lindsay’s SO team destroyed a stone viaduct

carrying the main railroad line between Germany, Austria and Italy, impeding

German reinforcements and supplies. From January to August 1994, Donovan’s

organization sent detachments of Yugoslavian-American Operational Groups,

together with some Greek-American and other OG sections, all of them trained at

Areas F, B, and A, to accompany British commandos on a series of raids on German

garrisons along the Dalmatian coast of Croatia.

There was a dual purpose in

this campaign. One was to draw off German troops who were being used in a major

offensive designed to crush Tito’s Partisans. The other purpose was to deceive

Hitler into thinking that the main invasion by the Western Allies might come in

the Balkans instead of France.259 Corporal Otto N. Feher, from Cleveland, the

son of Hungarian immigrants, was a member of the Operational Group team that

helped raid and defeat the German garrisons on the sizable islands of Solta and

Brac between Dubrovnik and Split. “They told us from the start, there’s no

prisoners. You get caught, you’re dead,” Fehr said.

He also reported that

nearly one quarter of his 109-member contingent (perhaps the contingent he

originally trained with) were casualties during the war. The raids, together

with the aerial attacks on German forces by Allied aircraft, assisted Tito in

narrowly escaping capture. The OSS also kept supply lines open from Bari by

which to sustain the Yugoslav Resistance.

The OSS effort in Yugoslavia was a success to the extent

that its support of the Resistance did help keep many German divisions there

and not at the main Allied fronts and it also helped rescue thousands of downed

Allied aviators and aircrews. But given the political decisions made by the Big

Three, Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt, the proportion of support went

increasingly and overwhelmingly to Tito’s Partisans instead of Michailović’s

Chetniks. In the summer of 1944, Tito’s Partisans were again on the

attack—against the weakened Chetniks as well as against the Germans. OSS

reestablished its contact with and support of Mihailović that summer, primarily

through a new unit created to help rescue downed airmen.

By the end of the war,

some 2,000 downed airmen had been rescued and evacuated via Chetnik or Partisan

controlled areas of Yugoslavia. The majority of these airmen were Americans

shot down during U.S. 15th Air Force’s bombing raids from Italy against the

heavily defended Axis oilfields and refineries in Ploesti, Romania. Most were

crews of B-24 “Liberator” bombers, but some were pilots of their fighter

escorts. OG member Otto Feher remembered the Resistance bringing in a Tuskegee

Airman, the first black pilot he had ever seen, who had eluded capture by the

Germans for several weeks.

Another 1,000 airmen had been rescued by OSS SO

in the rest of the Mediterranean Theater, a total of 3,000 skilled Allied

airmen rescued to fly again. Allied support of the wartime guerrilla

operations, first of the Chetniks and then of the Partisans, had included the

equipping of tens of thousands of guerrillas. They had held down 35 Axis

divisions, including 15 German Army divisions that might otherwise have been

deployed in Italy, France, or the Eastern Front.

But Allied favoritism towards

the Partisans and especially the Red Army’s direct assistance in the fall of

1944 helped Tito create a communist state in postwar Yugoslavia. Similarly,

although a small OSS mission worked with the rival communist and non-communist

resistance movements in tiny, neighboring Albania, primarily to rescue

survivors from downed American planes, it was the communists who came to

dominant the country in the postwar era.

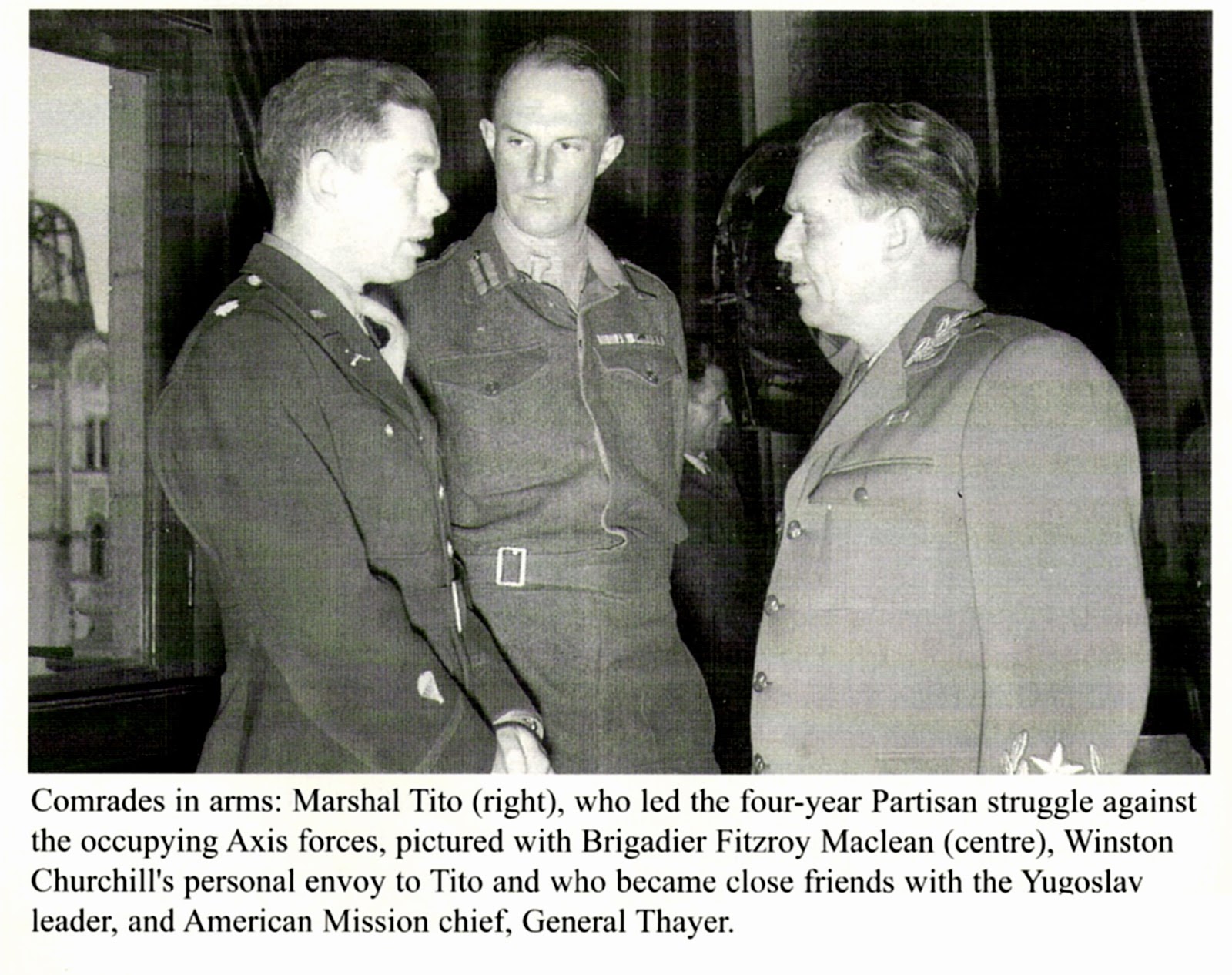

The

British viewed anti-Nazi partisan movements as potential allies and Churchill in particular

had a romantic conviction that special operations could undermine the German sense of military

superiority. In May 1943 the first British SOE operatives were parachuted into Yugoslavia to

liaison with the communist partisans led by Tito and the Chetnik royalists. With the surrender of

Italy in 1943 and the capture of Rome in 1944, the Allies were able to base planes at Bari and then later on the island of Vis, where they could directly supply the Yugoslav partisans.

Contact was maintained with the British forces on the ground through wireless and Sugar phoneportable radios that weighed about 30 pounds. The British mission in Yugoslavia was large and diverse. Its

main assignment was to support the activities of the partisans, many thousands of

whom were evacuated to hospitals and then, after treatment, returned to combat. Many well-known

public figures served in this SOE operation, among them Fitzroy Maclean, a former diplomat and

member of parliament; Randolph Churchill, the prime minister’s son; and the

novelist Evelyn Waugh.

According to one writer, “throughout the war, the delivery of 16,500 tons of

supplies and the evacuation of 19,000 people by special duty aircraft to the Partisans made the

difference between defeat and victory.” Overall, 8,000 sorties were flown into the

country. When one considers that by the end of the war over 13,000 men and women had been engaged by

the SOE in World War II, including many thousands in the Yugoslav operation, By the end of 1943, Anglo-American missions in Yugoslavia

numbered 65 people working with Draja a Mihailovic a Chetnik royalist with the communist-led

partisans. Partisan sources

dating from the end of September 1944 that mention personnel from the English

missions list 121 people, among them ten parachutists of Yishuv. However, only Sergeant Feigl (Dan Lšhner/Laner) is specifically labeled as a Palestinian.or perhaps because of

they were a small proportion of the Allied special forces personnel

inYuguslavia, the Yishuv parachutists get only two paragraphs in Heather

Williams book on the SOE in Yugoslavia.

However, several

non-Jewish soldiers from the OSS left accounts of the Jewish volunteers.

Franklin Lindsay

recalled Bill Deakin radio operator: His real name was Peretz Rosenberg, and

he was a sabra born in Palestine to German parents. His real objective was to

find out whatever he could find out about the situation of the Jews in Yugoslavia. Thirty-one year old

Deakin and Captain W. F. Stuart had parachuted into Yugoslavia in May of 1943

along with Peretz Rose (Rosenberg) in the first joint SOE-SIS (Secret

Intelligence Service, the British foreign intelligence agency) mission to Tito.

Sebastian Ritchie

recorded similar stories. Israel many archives provide a wealth of primary

documentation on the parachutists. Of particular importance are the Haganah

Archive, Israel State Archives, Central Zionist Archivesand Israel Defense

Forces Archive. But there are also several museums and local archives, suchas

Sdot YamÕs Hannah Senesh House, devoted to the parachutists. There is one

surviving member of the volunteer unit, Sara (Surika) Braverman of Kibbutz

Shamir in northern Israel,whom we interviewed for this article.

BravermanÕs story, although she was not the most activeof

the Jewish parachutists, led us to the Yugoslav sources. Nevertheless, the

Yishuv paratroopers own writings remain by far the most importantsource for

chronicling their time in Yugoslavia. These documents are, however,

problematic, because (with four exceptions) the paratroopers did not speak the

language of the partisans they worked with. They were not acquainted with the

regions geography.

Neither did they obtain anyknowledge of the local people

they met, and whom those people were fighting for or against. Atmost, they

understood the general picture that there were partisan bands fighting the

Nazis.Beyond this, the volunteers often remained ignorant of many aspects of the

situation around them.

According to histories of the parachute effort, 240 men and

women volunteered for themission.

Of these, 110 were trained, 37 were selected

and 32 actually participated. The British provided

the operatives with code names, such as Minnie for Szenes and Willis for

AbbaBerdiczew (pronounced Berdichev). Most of the volunteers were in their

mid-20s, with anaverage age of 28. The oldest was 44-year-old Aharon Ben-Yosef

of Bulgaria and their youngest member was Peretz Goldstein, who was only 21. All

had been born in Europe and almost half were Rumanian. Fourteen of them had

obtained citizenship in the British Mandate of Palestine (although for reasons

that are not clear,

few of the Romanians did).

Of the 32, almost two thirds were sent by MI9, the section

of the British Military Intelligence charged with rescuing pilots who had gone

down behind enemy lines.Most of the parachutists never carried out the missions

they were assigned. Many of themwere captured quickly, while others spent much

of their time attempting to reach theirdestinations. For instance, the five-man

team assigned to infiltrate Slovakia spent weeks at Bari awaiting for a plane to

take them to that country,, missing their target date. Many of the paratroopers

were captured, tortured, and killed. The British could be quite cold about

expressing regrets in such cases. A prime example is a letter about Peretz

Goldsteinsent by a British official to Teddy Kollek, who was the Jewish

Agencys liaison with the British.Ò have been instructed by Cairo to cease

payments to Private Goldstein, the official informed Kollek. According to our

latest information, he was arrested in July, 1944, deported to Germany and in

December 1944 sent to forced labour in an aeroplane factory. The question

of his present whereabouts is being pursued.

Photographs taken

during their training in Palestine and Egypt show them at a rail depoton the

way to Egypt or in a forest, wearing a lange uniforms and some in leather

flight jacketsand the others in standard-issue desert khaki fatigues with

berets. Seven volunteers were

originally slated to jump into Yugoslavia, which had been occupied by the

Germans, Italian, Bulgarian, and Hungarian forces in April of 1941.

Todays Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a part of Serbia were formed into

the fascist IndependentState of Croatia run by the fanatical pro-Nazi Ustasa destroy its perceived enemies, i.e. Serbs, Jews, Roma, and

antifascists.

Resistance movementsacross Yugoslavia emerged almost immediately primarily the Chetnik royalists and the communist Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito. Titos forces eventually dominated. By 1944 large parts of the country were liberated or semi-liberated.

The Allies invested a large effort to supportthese movements, originally in the framework of Winston Churchills call to set Europeablaze. Beginning in 1943, supplies were airlifted systematically from Italy to the antifascistforces. It was this organized operation, carried out in cooperation with two free armies withwhich the British had established close ties, that theoretically ensured an effective deployment ofJewish parachutists. Of the seven parachutists slated to operate in Yugoslavia, Reuven Dafni and Eli Zoharhad both been born in Zagreb. Shalom Finci came from the town of Kreka, near Sarajevo, and Nissim Arazi-Testa from Monastir (Bitola) in Macedonia, joined aswell. At least two of the others, Braverman and Yona Rozenfeld, had been born in Romania.

Resistance movementsacross Yugoslavia emerged almost immediately primarily the Chetnik royalists and the communist Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito. Titos forces eventually dominated. By 1944 large parts of the country were liberated or semi-liberated.

The Allies invested a large effort to supportthese movements, originally in the framework of Winston Churchills call to set Europeablaze. Beginning in 1943, supplies were airlifted systematically from Italy to the antifascistforces. It was this organized operation, carried out in cooperation with two free armies withwhich the British had established close ties, that theoretically ensured an effective deployment ofJewish parachutists. Of the seven parachutists slated to operate in Yugoslavia, Reuven Dafni and Eli Zoharhad both been born in Zagreb. Shalom Finci came from the town of Kreka, near Sarajevo, and Nissim Arazi-Testa from Monastir (Bitola) in Macedonia, joined aswell. At least two of the others, Braverman and Yona Rozenfeld, had been born in Romania.

Five volunteers were

to be sent to Slovakia, which in 1944 was in the throes of a revolt against the

Nazis that would eventually take the lives of around 20,000 Germans and

Slovakian rebels.Three Jewish volunteers were to be sent to Italy, two to

Bulgaria, three to Hungary (Szenes,Goldstein and Yoel Palgi) and nine to

Romania. Sergeant Peretz Rosenberg, who was among thefirst to be deployed, does

not appear on the British list of 31 Yishuv parachutists and theirdestinations,

probably because he was seconded as a radio operator to Deakins British

mission(SOE/ISLD-SIS) headquarters.

The facts on the ground dictated, however, that the largest

number of Palestine Paratroopers 14 would be sent into Yugoslavia, even if

their ultimate destination whasother countries, such as Hungary.

Yugoslavia also seems to have been the safest destination. Of those sent directly to other countries,12 were captured and seven executed among them Szenes in Budapest; Haviva Reik ,Rafi Reiss, and Zvi Ben Yaakov at Kemnika massacre ,Abba Berdiczew in Mauthausen; Enzo Sereni in Dachau, and Peretz Goldstein, captured in Hungary and murdered at Oranienburg concentration camp. Not a single Palestine paratrooper was captured or killed while in Yugoslavia. Many of those who died became national heroes of the young Israeli nation after the war.

Yugoslavia also seems to have been the safest destination. Of those sent directly to other countries,12 were captured and seven executed among them Szenes in Budapest; Haviva Reik ,Rafi Reiss, and Zvi Ben Yaakov at Kemnika massacre ,Abba Berdiczew in Mauthausen; Enzo Sereni in Dachau, and Peretz Goldstein, captured in Hungary and murdered at Oranienburg concentration camp. Not a single Palestine paratrooper was captured or killed while in Yugoslavia. Many of those who died became national heroes of the young Israeli nation after the war.

Enzo Sereni, was almost 40 when he died, had been born in Italy. Fleeing the rise of fascismin 1926,

he came to Palestine and helped found Kibbutz Givat Brenner. He was parachuted

intohis native Italy in May 1944, but landed near a German position and was

immediately capturedand sent to Dachau, where he was killed on November 18,

1944. His wife, Ada, went to searchfor him after the war in Europe, sending

home to Givat Brenner a cryptic note stating : Sorry the happy news completely

false, Enzo was murdered in Dachau. Hannah Szenes

parachuted into Yugoslavia in March 1944. She was captured while crossing the

border into Hungary, where she was put on trial for treason and executed by

firing squad in November of 1944. Zvi Ben-Yaakov. Rafi Reis, Abba Berdiczew,

Haviva Reik, and Haim Hermesh awaited transport to Slovakia from Bari in

southern Italy.

Conclusions

Our perusal of Yugoslav archival material, interviews, and

field study have shed light onthe actions of the volunteer Yishuv parachutists

sent by the British into Yugoslavia during WorldWar II. The mission, we show,

was confused and often inconsistent in its stated goals and theaction taken to

achieve them. It was chaotic and plagued by misunderstanding between the Jews,who

found themselves sometimes in a foreign world among people who did not speak

theirlanguage, and the Yugoslavian partisans, for whom foreign interests and

missions, includingJewish ones, were not a high priority.

Nevertheless, they

cared much more than the members ofthe Yishuv realized. While the parachutists

complained of a lack of sufficient assistance from the partisans, in fact the

Yugoslavian combatants did a great deal for them.I have attempted in my study

to mellow some of the contradictory details regarding whether the

European-born Palestinian Jews did or did not hide their identities and whether

the Yugoslav partisans understood who they were. It appears from the sources

that, although instructed to hide their identities, the cover stories they were

given would easily have given them away.

Thus the attempt to hide their

identities failed. However at the same time the Yugoslav partisans

seem to have

known little about them or expressed much interest in their real identities.It

is

important to understand that situation in which emissaries found themselves

in Yugoslavia was unexpected and complex. They found themselves deployed along

the main German retreat route from the Balkans. Failing to grasp complexity of

the situation, they persisted in pursinggrand but nearly impossible goals,

instead of smaller and achievable ones.

With partizans March 1944 ( Arazi front left , Rosenfeld second from right )

Peretz Rosenberg

Rosenberg

joined the paratroopers' parachute training, and in May 1943 under a false

identity ("Sergeant Rose")parachuted into the Zabljak area, in

the Dormitory Mountains of Montenegro, as part of British commando and

intelligence. Under the command of Captain Dean (FW Deakin) whose task was to

join the partisan group under Tito's command. Rosenberg served as the wireless

unit of the British unit and was the liaison officer from Tito Headquarters to British OSS Hdq inCairo. He coordinated the air dropping of explosives and more to the Tito partizans.

Due to his

many good contacts , Rosenberg also helped Tito people maintain their

communication equipment, thus creating a warm relationship between him and

Tito's team.

In November

1943, as part of the partisan forces, Rosenberg was present at the second

conference of the "Yugoslav Anti-Fascist Council for Liberation of

Yugoslavia" (today in Bosnia and Herzegovina), in which the Council

declared itself the supreme executive branch of Yugoslavia.

Immediately

after the conference, Rosenberg, with several wounded partisans, embarked on a

voyage back to the Adriatic coast, where they boarded a British torpedo ship

that took them to Bar

in southern Italy, and from there in flight to Cairo,

and then his seat, Nahalal.

At the

beginning of the War of Independence, he served in the science department and

assisted with Janke Ratner in various military developments, during which time

Peretz was asked at Aaron Remez's request to assist in establishing a wireless

connection in the air service, and his credit was credited without the

malfunction of the Black 1 weapon plane

Yona Rosenfeld

He was born

in Cluj, Romania. In his youth he joined the Zionist youth movement and was

elected its leader at the age of 16.

In 1939 he made an alia to British Mandate

Palestine, where he got on one of the illegal voyages with his wife. In Mandate Palestine, he became a member of the elite Palmach troops in 1942 and volunteered for a secret parachute mission in Europe.

In 1939 he made an alia to British Mandate

Palestine, where he got on one of the illegal voyages with his wife. In Mandate Palestine, he became a member of the elite Palmach troops in 1942 and volunteered for a secret parachute mission in Europe.

After completing special training, he jumped on March 14, 1944, over Yugoslavia, along with Hana Senesova, Abu Berdichev and Re'uven Dafni. Then they were to go to Hungary. However, Rozen failed to do so and returned to Egypt and then to Palestine. At the end of the Second World War he went to Hungary to help organize a belly (secret passage of Holocaust survivors to Mandate Palestine).

In 1939 he made an alia to British Mandate

Palestine, where he got on one of the illegal voyages with his wife. In Mandate Palestine, he became a member of the elite Palmach troops in 1942 and volunteered for a secret parachute mission in Europe.

In 1939 he made an alia to British Mandate

Palestine, where he got on one of the illegal voyages with his wife. In Mandate Palestine, he became a member of the elite Palmach troops in 1942 and volunteered for a secret parachute mission in Europe.After completing special training, he jumped on March 14, 1944, over Yugoslavia, along with Hana Senesova, Abu Berdichev and Re'uven Dafni. Then they were to go to Hungary. However, Rozen failed to do so and returned to Egypt and then to Palestine. At the end of the Second World War he went to Hungary to help organize a belly (secret passage of Holocaust survivors to Mandate Palestine).

Reuven Daphne was born in 1913 in Zagreb, Austria, called "Ruben Kandt." When he was 14, the family moved to Vienna, Austria, where he was first exposed to anti-Semitism and his affiliation with Zionism became stronger. He began attending a Jewish school, and learned Hebrew in order to immigrate to Israel and settle there. In 1936 he immigrated to Israel alone and was one of the founders of Kibbutz Ein Gev. Daphne enlisted in the British Army in 1940, serving in the RAF. On March 15, 1944, he was parachuted into northern Yugoslavia as part of a first group of four Jewish paratroopers: Reuven Daphne, Hannah Szenes, Yona Rosen and Abba Berdichev.

A

month later, Joel Pelagi and Peretz Goldstein were also joined. The delegation

was tasked with arranging the transfer of envoys to Romania and Hungary, and

Reuven Daphne was tasked with "staying in Yugoslavia and serving as a point

of contact between the outgoing members of those countries and the headquarters

in Bari and Cairo, and to operate in Yugoslav territory." Shortly before

leaving across the Hungarian border, Hannah delivered to Reuben the song of the

match, with a request that if she did not return, the song would be handed over

to friends in the sea. On New Year's Eve 1944 Reuben Daphne parachuted for the second time to Yugoslavia and on October 13 left Yugoslavia

completely. In March 1945 Daphne was discharged from his military service.

Dafni Egypt 1944 ( 2nd left back raw )

Dafni and Tito's partizans

Dafini with French Maj.Adami , Yugoslavia 1944

Dafni and Hermes sometime in 1945 ,Yugoslavia

Rehavam Amir Ziablodovsky

The course

must, at the same time, receive additional training for departure. Among other

things, he also participated in a parachute course, designed for agents who

volunteered to drop behind enemy lines, run by the British ISLD (Inter Service

Liason Department).

After delays

in the execution of the mission plan, in October 1943, about a month after his

marriage, the order was issued and Amir boarded a ship from Alexandria to Bari,

Italy. In Italy, he contacted the commanders of Eretz Israel camps in the city

of Salerno, on the border of the Allied territory, and transferred them a sum

of money from the Jewish Agency. He then returned to Bari, and from there on a torpedo boat arrived at Vis Island (VIS), which was controlled by Tito’s

partisans. The mission of the island was to join the ISLD representative on the

spot, and establish direct contact with the headquarters in Bari. During his

stay on the island, he contacted various forces that passed through him, including

with Israeli volunteers. He also met Jewish refugees who were smuggled into the

island by partisans. These refugees conveyed the news of soldiers from Israel

in Europe, and of the refugee camps set up in liberated southern Italy, and

which were handled by Israeli soldiers.

On Passover

1944, Amir returned to Bari for his departure on the original mission, where

he was also appointed a lieutenant . On the night of May 12-13, 1944 he was dropped in an

area controlled by partisans Ljubljana, Slovenia. His

mission there included: Tracing of a British mission that parachuted into the area and contact was lost with ; Dealing with the refinement

of methods of linking partisan headquarters, and training partisans with

communication and encryption methods;

Having direct wireless contact with

the SOE headquarters in Bari.. He spent several

months in the area, after which he flew back to Bari for three weeks, and

returned to the area with supplies and new equipment. In late 1944, after 3

missions across enemy lines, Amir returned to his homeland in Israel.

Showing a W/T to Yugo Partizans 1944

Eli Zohar

Passover Haggadah that was used by Jewish soldiers on 8 April 1944, at a Seder on a British base for soldiers from Eretz Israel in Bari, Italy

On the inside cover are the signatures of five paratroopers from the Yishuv: Rehabeam Zabludovksy-Amir, Yaaqov Shapira, Shalom Finzi, Eli Zohar and Peretz Rozenberg-Vardimon. In addition, there are signatures of Jewish soldiers in the Allied Forces, a Jewish member of the Italian underground and others In addition, there are signatures of Jewish soldiers in the US Armed Forces and Jewish members of the Italian underground

In contrast to these accounts is the case of Eli Zohar.

Zohar, born Mirko Leventhal inZagreb, was one of the parachutistsÕ only members

to come from Yugoslavia and speak thelanguage of the partisans. Ivan Sibl was a political commissar of the Tenth Corps. (Reuven

Dafni) accused Sibl of being the main reason for the prolonged stay of the

volunteers among the partisans, which hindered their mission. Dafni thought that Sibl was a half-Jew. Zohar offers a humorous anecdote,

another one involving an amateurish cover story. He relates that he was introduced to Sibl as Eli Joel, Sergeant only to find himself greeted in

Serbo-Croatian by Sibl who told him you are not Eli Joel, you are Mirko

Leventhal, my friend from high school. But,on the same occasion, Sibl met Hanna Senesz and, in his diary, described her as

British.

Later on a group of

ten Jewish refugees from Hungary came to the partisans, fleeing fromthe

Germans. Among them were three young women whom Eli Zohar apparently knew from

before the war. He asked to see them and was allowed, in the presence of the

officers of OZNA.(OZNA was the Department for the Protection of the People, in

fact a Partisan security service. It was established on May 13, 1944, meaning

that this encounter occurred after that date.)

Zohar questioned the refugees in

the presence of the partisans. He seems to have met one of the girls a few more

times following that encounter. According to Dr. Rua Blau Franceti , all three of the girls were later arrested by the partisans

and executed as British spies. This story includes

one issue that may shed light on its veracity.

The relationship between the

British and partisans worsened in the fall of 1944 and the British missions were

under suspicion that only grew with time and another related issue. Since the

counter-intelligence work of these partisan units was under the control of the

intelligence officer of Tenth Corps who is believed to have been a German/Ustae spy, it may be that he used this as an excuse simply to get

rid of Jews and to deepen themisunderstanding between the British and

partisans. This facts of this horrendous betrayal require further study-

Nissim Arazi (Testa )

Nissim was born in the town of Bitola, in the state of Macedonia in Yugoslavia, on August 20, 1717. His parents Sol and Moshe Testa. In his youth, he was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement and the founding members of the movement's city of Bitola. After graduating from the gymnasium, he enlisted in the artillery corps in the Yugoslav army, and upon his release joined training on an agricultural farm in preparation for kibbutz life. In 1939, when he was 22, he immigrated to Eretz Israel, thus surviving the Holocaust in Europe. His older sister and younger brother perished in the Holocaust.

Nissim Arazi immigrated to Israel as an illegal immigrant, managed to sneak through the British Army Guards and joined Kibbutz Sha'ar Ha'emakim where he was a wagoner and worked in agriculture. In 1943, he enlisted in the British army and volunteered to serve in the parish unit of the Jewish community trained by the English to parachute in Europe beyond the Nazi enemy lines in the hope of rescuing British prisoners and pilots who abandoned their aircraft during the war.

Nissim took a parachute course at the RAF Ramat David, and a wireless and liaison course at Kibbutz Ramat Hakovesh. To complete his training, he was sent to Cairo where he was given a pseudonym: Isaac Arazi. Upon the establishment of the state he adopted this name for his official surname. Parachuted into Yugoslavia in the spring of 1944 and broke his leg while parachuting, despite his injuries he joined the partisans and fought with them for 3 months with a legged leg mounted on a white horse. While fighting he sent broadcasts to the British and helped them in their war against the Nazis. In the area where Yugoslavia operated, no Jews were found who had to be rescued. The few Jews remaining in the area may not have dared to identify themselves as Jews.

Dan Lanner

נולד באוסטריה בשם ארנסט לינר, היה חבר בארגון הנוער הציוני בלאו וייס. בשנת 1938, לאחר סיפוח אוסטריה על ידי גרמניה הנאצית נמלט מהמדינה. בשנת 1940 עלה לארץ ישראל, ונמנה עם מקימי קיבוץ נאות מרדכי. בשנת 1941 התנדב לפלמ"ח וגויס למחלקה הגרמנית, שהתאמנה לפעולות מאחורי קווי האויב. בשנת 1944 הוצנח על ידי הבריטים ביוגוסלביה, שם לחם בשורות הפרטיזנים של טיטו. לאחר תום מלחמת העולם השנייה חזר לארץ ישראל. בשנת 1946 עבר קורס מפקדי מחלקות של הפלמ"ח. בהמשך מונה למפקד הגדוד הראשון של הפלמ"ח

נולד באוסטריה בשם ארנסט לינר, היה חבר בארגון הנוער הציוני בלאו וייס. בשנת 1938, לאחר סיפוח אוסטריה על ידי גרמניה הנאצית נמלט מהמדינה. בשנת 1940 עלה לארץ ישראל, ונמנה עם מקימי קיבוץ נאות מרדכי. בשנת 1941 התנדב לפלמ"ח וגויס למחלקה הגרמנית, שהתאמנה לפעולות מאחורי קווי האויב. בשנת 1944 הוצנח על ידי הבריטים ביוגוסלביה, שם לחם בשורות הפרטיזנים של טיטו. לאחר תום מלחמת העולם השנייה חזר לארץ ישראל. בשנת 1946 עבר קורס מפקדי מחלקות של הפלמ"ח. בהמשך מונה למפקד הגדוד הראשון של הפלמ"ח

Shalom Fintschi + (1954)

Born in:

Karaka, Bosnia Herzegovina

On:

12/03/1916

Army

service: United Kingdom SOE

Position: Paratrooper

Died in memorial disaster Kibutz Maagan 1954

He was born

in Kreka, Bosnia, March 12, 1916. At an early age he joined the Hashomer Hatzair

youth movement in Yugoslavia. He studied the profession of jesting at the

request of the movement, and was a member of the movement's chief leadership in

Yugoslavia. Joined the Yugoslav Army, and after his release, underwent training

at the Hashomer Hatzair agricultural farm prior to immigrating to Israel.

In 1939,

illegal immigration rose independently. He joined the training in Kibbutz

Sarid, and worked in paving the road to Bisan (later Beit She'an) and other

roads in southern Israel.

In 1941, he

volunteered for the Palmach, passed a commander's cum laude course, and, thanks

to his occupying personality, recruited many to the Palmach ranks.

In 1942, he

and two other friends, Dov Glazer and Moshe Sela, set out to plow the lands of

the Kibbutz designated Gat's existing foundation, near the Arab village of Iraq

al-Manshiya, and formed friendships and mutual respect with the Arab community.

After three months, the rest of the kibbutz joined a permanent settlement,

after a long stay of several years of training and waiting in Kfar Saba.

On February

6, 1943, he volunteered SOE Palestine - parachuting beyond enemy lines, with

the intention of the Jewish community to help save the Jews of Europe occupied

by the Nazis. He was chosen from among hundreds of volunteers for the paratrooper group of the Jewish Yishv, numbering 37 men and women recruited into the British

Intelligence Corps. The Brit SOE assigned him and his friends to act as

informants in the occupied countries: to report on what was happening in real

time through a wireless device they had, to report and rescue allied pilots

whose aircraft were dropped in those countries. For this purpose he was trained

in operating a wireless device and gathering information in enemy territory.

His cover name was Beno Pink.

He gone through parachute training in RAF Ramat David and RAF Fayida Egypt and then (Carthage),

Tunisia. There he was on standby for the Yugoslavian missions which were repeatedly cancelled due presonal security reasons. Fintschi was transferred, along with the group of Palestine paratroopers to the city of

Bari and the island of Vis, near Croatia, which which was freed from the German occupation. Island of Vis served also as an emergency base for 15th Air Force planes returning from missions over Germany , Austria , Romania and Bulgaria.

In July

1944, after about a year and a half of training and waiting, he parachuted into

Mikleuš in Croatia, and from there he walked 150 km through areas controlled by

the Germans, to the village of Vučani in the Moslabina region of Croatia, where

he joined the partisans. At some point he also joined the SOE Capt.Maurice Sutcliffe's team which included also Abba Berditchev.

First, kneeling from left , Croatia 1944 along with Capt.Sutcliff and Berditschev

In the

Moslava region, the partisans move between the mountains and the villages,

fighting and evading the Germans. Participated in battles, and radioed details

to what was happening to SOE Cairo. He met American pilots whose

aircraft were hit by the Germans AA, and luckily parachuted into territories

that were then under the control of partisans.

First right kneeling with Capt.Sutcliffe's team

On March

27, 1945, before the end of the war, when news of the rapidly advancing Red

Army and the retreating Germans arrived, he left with the commander of the British mission in Croatia Capt.Sutcliff on a plane carrying wounded to Italy, terminated

his service in the British army and returned to Kibbutz Gat.

Upon his

return, the kibbutz was chosen "to Mukhtar" who maintained contacts

with the surrounding Arab villages. In 1946, he married Zehava Kuhn, a refugee

from Croatia, who was rescued on the Kastner lifeboat that arrived in

Switzerland, and from there immigrated to Israel, joining her friends from the

movement who were on Kibbutz Gat.

On November

11, 1948, as commander of the kibbutz, he hosted the southern front commander

of Yigal Alon during his historic meeting with Gamal Abdel Nasser, later

Egypt's president, in negotiating a ceasefire agreement with the Egyptian army

in the Fallujah pocket near Kibbutz Gat.

In 1950, he

and his family set out on a mission in France to La Roche near the city of

Lyon, to a farm intended for the absorption of youth from North Africa and

their training for work and settlement in Israel.

On July 29,

1954, he along with his other ex SOE friends was killed in the Maagan disaster, at a memorial ceremony for the

paratroopers held on the shores of the Sea of Galilee in Kibbutz Maagan, when

a Piper Cab which spread greetings on the occasion, crashed into the crowd.

OSS / OSE Aid to the Chetniks

The British

recognized the Yugoslav government-in-exile and were anxious to help the

Cetniks, but could not provide more than token support. The Special Operations

Executive (SOE),

charged with encouraging resistance throughout Europe, had only four B-24s

earmarked for supply operations in Yugoslavia and Greece. Between March 1942

and January

1943, these aircraft flew twenty-five sorties, mainly to Greece.

On September

19, Brigadier Fitzroy Maclean--"a man of daring character"-parachuted

into Tito's headquarters in western Bosnia. Maclean arrived less than two weeks

after Italy had surrendered to the Allies. At first, the Partisans gained

substantial territory and a good deal of military equipment from the defeated

Italians.

OSS officers consult with Cetnik

leader Mihailovic

During this

three-month period, only 125 tons of supplies were air-dropped to Partisans and

Cetniks. Meanwhile, British disillusionment with the Cetniks deepened.

Brigadier Maclean thought that the time had come for the Allies to shift all

support to the Partisans. '"e were getting . . . little or no return

militarily from the arms we dropped to the Cetniks," he observed,

"which had hitherto exceeded in quantity those sent to the

Partisans."

In fact, arms delivered to the Cetniks were

more likely to be used against the Partisans than against the Germans. "On

purely military grounds," Maclean concluded, "we should stop supplies

to the Cetniks and henceforth send all available arms and equipment to the

Partisans." This shift in Allied policy was confirmed at the Teheran

Conference.

A secret

"military conclusion," initialled on December 1, 1943, called for

support of the Partisans with supplies and equipment "to the greatest

extent possible." Also, shortly after the first of the year, the British

ordered their liaison officers to cease contact with Mihailovic's forces.

"We have proclaimed ourselves supporters of Marshal Tito," Churchill

told the House of Commons, "because of his massive struggle against the

German armies.

The Army Air Forces Behind Nazi Lines

Throughout

1943, the British conducted aerial resupply of Yugoslav, Albanian, and Greek

resistance groups. In January 1944, however, Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker decided that

Americans should "get some credit in delivering knives, guns, and

explosives to the Balkan patriots with which to kill Germans." The wishes

of the newly appointed commander of the Mediterranean

Allied Air Forces led to the assignment of two troop carrier squadrons from

Twelfth Air Force to the Balkans supply effort. On February 9, the 7th and 51st

Troop Carrier

Squadrons of the 62d Troop Carrier Group were placed on detached service with

the 334 Wing of the RoyalAir Force (RAF).

These Army

Air Forces (AAF) squadrons, with an authorized strength of 24 aircraft,arrived at

Brindisi on the southeastern coast of

Italy on February 12. "Brindisi is a quiet

town," observed a member of the 7th, "with one treelined main

stem." There were

many British soldiers and airmen in town, but few Americans. Two cinemas

offered entertainment, along with service clubs that featured

tea,

biscuits, and sandwiches. Evenings were a bit livelier: the airmen could drink the local wine while listening to

Italian bands.

As it turned

out, there was ample time for leisure activities because the weather caused

numerous sorties to be canceled. The story of the 7th Troop Carrier Squadron

was typical. The squadron's pilots and navigators flew for three days with RAF

crews for familiarization. On the afternoon of February 16 operations orders came down from Group:

four C-47s would drop

on targets in Yugoslavia codenamed STEPMOTHER and STABLES. The designated

pilots and navigators studied detailed maps and located the drop zones. At 1930

hours, the

crews were briefed on the mission by British officers. RAF navigators would fly

with their American counterparts to assist in locating the targets. The four

C-47s were loaded with

their cargo, and the crews were tense with excitement. At 2145 hours, however,

Group informed the flyers that the mission had been canceled because of poor

weather conditions. "Everybody was plenty browned off," commented one

squadron member.

Unfortunately,

the weather failed to improve. Missions were scheduled, aircraft loaded, and

crews briefed, but cancellation followed cancellation. "We've been here at

Brindisi just about

two weeks now," lamented one airman on February 23, "and have yet to

complete a tactical mission." The next day the situation changed, when two

C-47s dropped 4,496 pounds

of propaganda leaflets (called "nickels") over Balkan Area Served by

AAF.

With all the

preparation, the leaflet drop seemed anticlimactic, as it was only necessary to

find the country, not pinpoint a drop zone. Late in the month, 7th Squadron

received orders to infiltrate a group of American meteorologists and equipment

into Yugoslavia. The AAF wanted better weather data both to assist bombing operations

by the Fifteenth Air Force against enemy targets in Central and Eastern Europe

and to improve the efficiency of resupply efforts in the Balkans.

Operation

BUNGHOLE

Major Jones,

however, managed to let down through the overcast. Breaking out at 3,000 feet,

he spotted eleven signal fires in the shape of a "V"-the required

recognition signal. Jones then

made four circling passes, dropping the meteorologists and their equipment.

Landing safely in the snow, the weather team--consisting of Capt. Cecil E. Drew

(forecaster),Sgt. Joseph J. Conaty, Jr. (observer), and a radio operatormade

contact with local Partisans and were escorted to Drvar, where they would be

attached to OSS mission CALIFORNIA. Soon the team began taking four

observations a day, which were coded by means of two cipher pads and transmit10

ted to Bari. The OSS later deployed six more meteorological teams to the west

and northwest of Drvar.

Also in late

February, the 51st Squadron conducted Operation MANHOLE, a special mission to

transport Russian military representatives to Yugoslavia. Air staff planners at

334 Wing ruled

out an airdrop or landing on the newly opened but snow-covered strip at Medeno

Polje, ten miles north of Drvar in western Bosnia. Instead, they launched a daytime

glider mission. At 0945 hours on the 23d, three C-47s from. the 51st departed

Bari, each with a Waco CG-4A glider in tow. Escorted by thirty-six fighters,

the transports proceeded to the reception area at Medeno Polje.

Despite

near-zero visibility, the gliders-and their cargo of twenty-three Russians and six

British officers-landed safely. The three C-47s then successfully dropped

10,500 pounds of supplies for the mission. AAF resupply

operations began in earnest in early March 1944. Every night C-47s flew

missions to Yugoslavia, Albania, and Greece, dropping supplies,leaflets,

and people (known as "Joes"). Returning to Brindisi after a long night,the

aircrews received "a good hooker" of straight rye whiskey,were debriefed by intelligence officers, then were

served a breakfast that often featured fresh eggs, a wartime rarity.

During six

weeks of detached service with 334 Wing in February and March 1944, the two

squadrons of the 62d Troop Carrier Group completed eighty-two sorties and

dropped 374,400 pounds of supplies to resistance groups in the Balkans. "We

delivered the goods," summarized the 7th Squadron's historian, "at the

right place, on time, to the right people, well behind Nazi lines of defense.

Rescuing

Downed Airmen

headquarters

at Drvar to arrange assistance in rescuing American flyers. Following a meeting

with Tito on January 23, orders went out to all Partisan units to do everything

possible to locate downed airmen and conduct them safely to the nearest Allied

liaison officer. Popovich, an engineer, then supervised the construction of an

airstrip at Medeno Polje, north of Drvar.

In

mid-April, Farish and Popovich parachuted into Macedonia, landing near Vranje

(north of Kumanovo), close to the Bulgarian border. They had a threefold

mission: to arm and supply

Partisan units, to report German troop movements,and to evacuate Allied airmen.

Having secured the cooperation of the local Partisan leader, who turned over to

them

four airmen

who had been sheltered in the area since the first Ploesti raid in August 1943,

the two OSS officers made their way north to contact Petar Stambolic, commander

of Partisan

forces in Serbia. With the enemy in pursuit, the journey took two weeks.

Stambolic immediately pledged his support.

On the night of June 16, after much hardship,

Farish and Popovich evacuated thirteen American flyers from an airstrip in the

Jastrebac Mountains, north of Prokuplje. While operations in Partisan-held

territory were hampered only by the enemy, efforts to retrieve aircrews from

Cetnikcontrolled areas ran afoul of the tangled web of Balkan politics. The

British, who considered that part of the world within their sphere of interest,

had shifted their support to Tito and were determined to sever all ties with

Mihailovic lest they offend the Communist leader.

American

attempts to maintain contact with the Cetniks had been rebuffed by London.

Nonetheless, Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining, Commander of the Fifteenth Air Force,

was determined to rescue his downed airmen. On July 24, 1944, thanks to the

efforts of Twining and

several OSS officers, General Eaker directed the Fifteenth Air Force to

establish an Air Crew Rescue Unit (ACRU). This independent organization of the

Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, attached to the Fifteenth Air Force, would be

responsible for locating and evacuating Allied airmen throughout the Balkans.

Having neither an "intelli29 gence" nor a "liaison" function,

it softened British objections about contacts with the Cetniks.

Donald Smith(right ) 451st BG with a Chetnik, June 1944

On the

evening of August 2/3, 1944, after several abortive attempts, Musulin and two enlisted men

parachuted into Mihailovic's headquarters at Pranjane, fifty-five miles south

of Belgrade. Musulin learned that some 250 Allied airmen awaited evacuation. As

nearby German garrisons no doubt would soon learn about his mission, the OSS

officer realized he had little time to waste.

Unfortunately, the only available

airstrip was on a narrow plateau on the side of a mountain, and it was far too

short for C-47 operations. Using 300 workmen and sixty ox

carts, the Cetniks managed to lengthen and widen the dirt strip to 1,800 by 150

feet. Though the airstrip was still marginal, there was no choice but to attempt

the evacuation.Six

C-47s from the 60th Troop Carrier Group left Italy on the evening of August 9.

Two planes turned back with engine trouble, but four managed to land on the

tiny strip. Restricted to twelve evacuees per aircraft, the group departed

around midnight, carrying out the first forty-eight airmen.

OSS Capt Nick Lalich (center )

The War

Diary of the 10th Troop Carrier Squadron rightly termed the operation

"extremely hazardous"-one that called for "the utmost in flying

skill and teamwork." 30 Just after dawn, six more C-47s arrived, with an

escort of twenty-five P-51s. While the fighters attacked targets in the local

area to give the impression that a normal air strike was in progress, the

transports landed, picked up another group of joyful evacuees, and departed. An

hour later, a second wave of six C-47s and fighters showed up and repeated the

process. In all, the morning's work brought out 177 American airmen, plus a few

other Allied personnel. A delighted Colonel Kraigher seemed to be

"floating around in the air four feet above the ground." Three more

missions were flown to Pranjane, two in August and one in September 1944,

retrieving another 75 American airmen.

September

also marked the beginning of a major Partisan offensive against the Cetniks.

This forced the Air Crew Rescue Unit to locate a new landing site to evacuate

airmen who continued to

fall into the hands of Mihailovic's hard-pressed followers. The experience of

Sgt. Curtis Diles, a B-24 nose gunner of the 455th Bomb Group, was typical of

many during this period.

On September 8, just after a bombing run on a bridge north of Belgrade, an

antiaircraft shell exploded under the flight deck and severed the B-24's

control cables.

Nine crew

members managed to bail out: one man was immediately captured by the Germans,

and Cetniks picked up another whose knees were full of shell fragments and took

him to a hidden hospital. Sergeant

Diles and three others landed close together and were welcomed by local Cetniks

"with open arms." Three days later they were joined by three more of

their crew members. The group then traveled together until they reached an

emergency landing area at Kocevljevo on September 17.

Gen.D.Mihalovic

Along the

way, Diles became impressed with his treatment by the Cetniks. He even had the

opportunity to speak (through an interpreter) with General Mihailovic. The

Cetnik leader

seemed to be a humble, honest man, genuinely concerned about his people. One

could tell by the tone of his voice, Diles recalled, that he spoke with

conviction. On the afternoon of the 17th, two C-47s arrived to pick up Diles,

his six fellow crew members, and thirteen other downed airmen.

The tiny

emergency strip, located on a meadow, had a downhill slope that ended in a

stand of trees. Happily, both aircraft managed to land safely, and Sergeant

Diles and his companions were soon on their way to Italy. The last HALYARD

mission took place on December 27. Two C-47s, one piloted by Colonel Kraigher

and the other by 1st Lt. John L.

Dunn, left Italy at 1100 hours. Escorted by sixteen P-38s, they reached an

emergency landing field at Bunar at 1255 hours.

Spotting a

hole in the overcast, Kaigher led the way to land on a 1,700-foot strip that

was frozen just enough to support the weight of a C-47. The airmen were met by

Capt. Nick Lalich, an OSS officer who had replaced Musulin as head of the

HALYARD mission in August. The transports were quickly loaded with twenty

American airmen, one U.S. citizen, two Yugoslavian officers, four French army

and four Italian army personnel, and two remaining HALYARD team members. The

aircraft took off at 1315 hours, marking the end of an extraordinarily

successful project: between August 9 and December 27, a total of 417 personnel

had been flown out of Serbia, including 343 American airmen.

Pranjane

Comments

Post a Comment